Joseph Kosuth

“Guests anf Foreigners: Rossini in Turkey”

Borusan Art Gallery

15 September – 28 October 1999

Joseph Kosuth, the reknown artist of Conceptual Art conceived and realised an installation entitled “Guests and Foreigners: Rossini in Turkey” for Borusan Art Gallery.

At the end of the 70’s Joseph Kosuth had a special recognition in Turkey. Young artists of the period were influenced by his ideas and work. He helped free them from the aesthetic burdens of early and late modernism. 30 years later, another young generation have almost the same expectations of that era. They want to be illuminated by experienced artists, to have a safe direction within the increasingly complicated art world and to absorb heterogene impulses of post-modern art. To the extent that the qualities and references of Conceptual Art are concealed in the oeuvres of today’s artists, this exhibition will provide a ground for re-cognition and re-comprehension for the viewer. With his intertextual and emancipatory installations Kosuth reveals his political, social and cultural confrontations and transmitts the ideas of many intellectuals as well. The selected texts in “Guests and Foreigners: Rossini in Turkey” will doubtlessly engage the artists and viewers with their intertwined implications.

Catalogue Text

For a very long time in Turkey, art has been understood and perceived as the faithful or analogous representation of reality and sense. Artistic activity has been either locked into “art for art sake” or into “art for society’s sake” by the artists who were mainly educated in the Academy of Fine Arts following the style of Modernism. Abstract painting and sculpture competed with realistic or fantastic figurative painting and sculpture. Even in the middle of 70’s most of these artists were “studio artists” and did not incorporate the current transformations and movements of Western art into their artwork, which opened the way to reconstructing the relationship between the artist, the space, the artwork and the viewer. Furthermore, because of incongruity between political, economic and technological developments, new resourceful links between art, current concepts and philosophy were to be achieved.

A kind of zeitgeist came towards the end of the 70’s, mainly induced and provoked by the teachings and productions of a group of younger artists who could observe the transformations in Western art manifested in Conceptual, Minimal and Pop Art. However, violent struggles in Turkey towards a better democracy, which ended up in two military coups in 1960 and 1970, have also prepared a ground for political as well as cultural antagonists and protagonists. These artists started to question the relationship between the artist and the public and to look into the function, reception and perception of artworks within the context of the ideological polarizations of extreme left and right and the unitary state capitalism. They were aware that the art of their teachers was not only cut off from the society, but also from the world around them. In that world artists were questioning art and its relation to the real world; and the real world, they were realizing, was being decentered, deconstructed and differentiated. They had to follow one of the paths paved by the prominent Western artists of 60’s and 70’s.

Paradoxically, one of the most remote, and at the same time one of the most relevant paths, was that of Kosuth. It was remote because its practical and theoretical, if not to say philosophical, orientation was based on a mix of theories that used language itself as a model and source (Wittgenstein, Benjamin, Borges, Saussure among others) and, was originally not well-received in the western art world, much less Turkey. On the other hand, it was relevant, because Kosuth dealt with sign and language and not with image and representation. Considering the fact that Turkish artists had an iconoclastic tradition, and, calligraphy was the supreme expression, this was a familiar way for them to make art. Moreover, Kosuth was the one who was asking crucial questions about how art works and functions within culture, and thus, changing the role of the artist. At the end of the 70’s, in Turkey it was almost inevitable to make this change and liberate the artist from his/her burden of distorted taste, that exhausted modernist tradition of formalism. Later, when Kosuth started his site-specific and culturally specific works, with the use of art as a conveyance between languages and cultures– and indicating the sameness, within difference, of –language– he became more important for the artists in Turkey, who wanted to break through their isolation and learn efficient ways of transmitting their ideas.

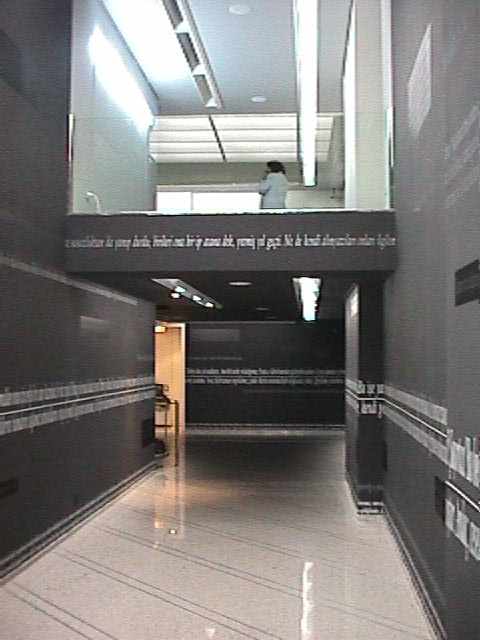

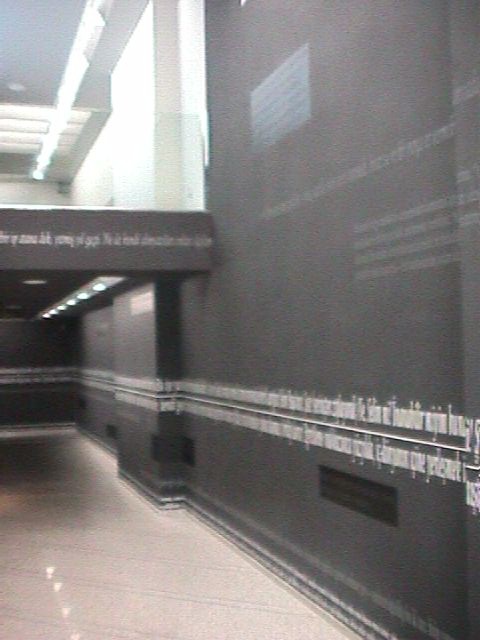

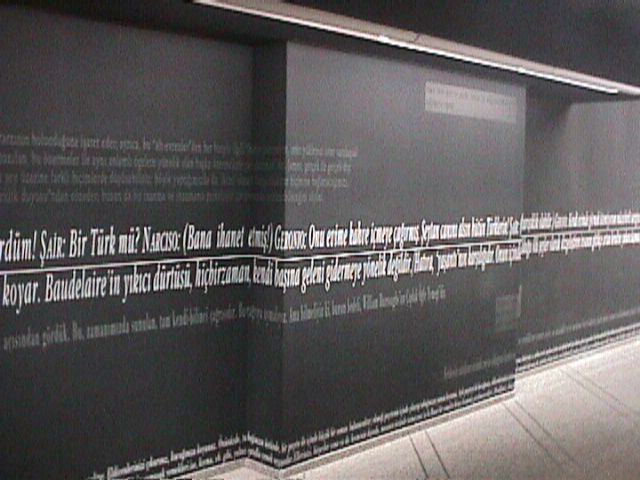

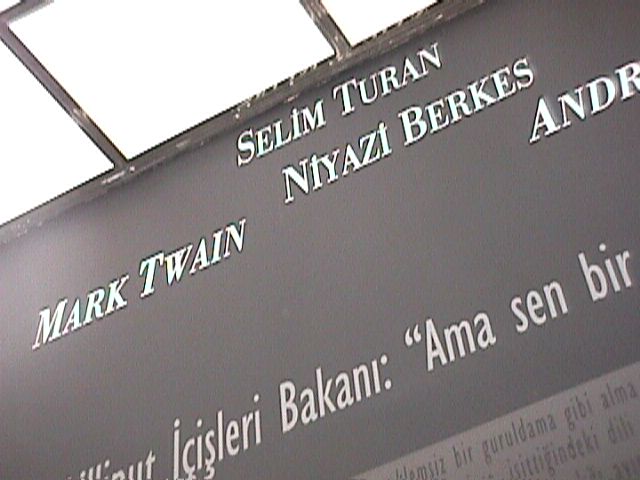

For two decades Kosuth influenced artists in Turkey from afar. Better late than never, we have succeeded in inviting him to come to Istanbul and work in the Borusan Art Gallery. In less than ten days he has transformed the corridor-like gallery space into a cathedral of texts, which were painstakingly placed on the dark gray walls in circumfluent rows and cadenced blocks. The names of philosophers, artists and intellectuals who migrated to and from Turkey crowned this conglomeration of words. The space embraced a fragmentation and a wholeness at the same time, a significant duality, which is obviously one of the goals of Kosuth.

For the ordinary viewer in Istanbul, Kosuth’s major contribution as an artist seems to be the combination of the realm of the ‘word’ with the realm of the ‘space’. Even this aspect of his work was not strange to the viewer who could appreciate the correspondence between the traditional religious spaces, where calligraphic texts divulge the realm of the divine meaning. The viewer could also acknowledge and perceive that different texts have been analyzed, fragments have been chosen, relations between the fragments have been detected and the emerging conceptual phenomena was controlled by a holistic system invented by the artist. With all these scepters it has challenged the prevailing modernist gaze and its framing ideologies.

Kosuth’s Proto-investigations, as displayed in the mezzanine of the gallery, were fundamental within the Western socio-political and cultural context of the 60’s, when new linguistic and ideological theories attacked the fundamental presumption of modernism, when modern philosophy was deconstructed, when differences became more significant than unities and identities, and when centralized and totalistic meaning was released and disseminated. For the non-Western world however, these changes were still unknown and alien, but even then Kosuth’s early work had incited excitement and vigor here. Because they proposed a tabula rasa, they promised a new order and investigated the real creative process. As for his recent holistic investigations, which are quintessential within the global culture of the 90’s, it is predictable that his work is perceived and affirmed effortlessly, due to the fact that the non-West is more aware of its pivotal position and function in the global context. While the intertextuality of the work gives hope and freedom for any kind of spiritual and intellectual emancipation, his insistence on working with the language of the country where his work is shown, imparts to him the reputation of being non-colonialist, which according to the true rules of globalism is an noble attitude.

The texts he has chosen for this project have an interwoven logic in itself, yet the installation refers to different historical and current facts. First of all, it is related to his corpus of work developed since 1992, when he participated in a group exhibition in Linz, entitled The Foreigner/The Guest. Installations at the Venice Biennale in 1993 entitled ‘Zeno at the Edge of the Known World’ and in Como entitled ‘Rules and Meanings” have patterned the background for ‘Guests and Foreigners’ realized in Oslo at the Kunsthernes Hus and in the Frankfurt Schirn Kunsthalle.

The location of the Borusan Art Gallery in the Beyoglu district of Istanbul, where at the beginning of the century minorities like Armenians, Greeks and Jews, and emigrants from Russia lived and where the foreign embassies have located their palaces, offered a perfect milieu for this installation.

After the 50’s the district has under went a radical transformation. The one time owners of the neo-classical and art-nouveau architecture gradually left Turkey and emigrated to Europe and USA, and since then the new inhabitants emigrating from the remote villages of Anatolia are trying to merge their rural culture with the remains of the Beyoglu culture.

However, since the beginning of the 90’s the main street is changing its face from destruction to renovation, from commodity to culture. Borusan Cultural Center, with its philharmonic orchestra, contemporary art gallery and music library is one of the major investments to Turkey and its culture. Considering that music is the basic activity of the Borusan Cultural Center, music, as represented by Rossini, became the core of Kosuth’s installation in Istanbul. Again, Rossini’s appearance is not coincidental. Goethe’s Italian Journey and Rossini’s opera The Turk in Italy were the two links which locked the chain of functional components. The word “Turks” repeats itself in the libretto, which is placed on top of the horizontal line along the walls, indicating their dubious position as guests and >foreigners in Italy.

Judging from intricate texts he has chosen, one might think that Kosuth takes the high role of a public philosopher. No, he does not take such a distance from the viewer. Seeing him work in the gallery as he coordinated the assemblage of the work, as he conscientiously answered the questions of reporters, all of us realized that he had wider concerns about the country where he was a guest artist; we understood that the combination of the texts enveloped more than the discourse he constructed since the beginning of this series of work, namely his insight and understanding of the socio-political and cultural milieu and dilemma of Turkey. During the installation days he evidently was counteracting any kind of mystification and manipulation of the art production experience. Modest artists are still deeply respected in Turkey. It is not arbitrary that he selected those words of Goethe which carries inspirations of Eastern philosophy: “And until you have grasped this ‘Die and be transformed!’ you will be nothing but a somber guest on the sorry earth.”

Beral Madra

Katalog Metni

Türkiye’de çok uzun süre sanat gerçeğin ve duygunun sadık temsiliyeti ve benzetisi olarak anlaşılmış ve algılanmıştır. Sanatsal eylem, Güzel Sanatllar Akademisinde eğitim görmüş, Modernist uslupları izleyen sanatçılar tarafından ya “sanat için sanat”a ya da toplum için sanat”a kenetlenmişti. Soyut resim ve heykel figüratif resim ve heykelle yarışıyordu. 70’li yılların başlarında bile bu sanatçılar “atölye sanatçıları”ydı ve Batı sanatındaki, sanatçı, mekan, sanat yapıtı ve izleyici arasındaki ilişkilerin yeniden yapılanmasına yol açan güncel değişimleri ve akımları sanat yapıtlarının kapsamına almıyorlardı.Ayrıca, siyasal, ekonomik, teknolojik gelişmeler arasındaki çatışkılar yüzünden sanat, güncel kavramlar ve felsefe arasında da yeni yaratıcı ilişkilerin kurulması gerekiyordu.

Bir tür “zamanın ruhu” durumu 70’li yılların sonuna doğru, Batı sanatında kendini Kavramsal, Minimal ve Pop Sanat’da gösteren değişimleri gözlemleyebilen bir grup genç sanatçının eğitim ve üretimleriyle oluştu ve gelişti. Ancak, 1960 ve 1970 sonunda iki askeri darbeyle sonuçlanan daha iyi bir demokrasiye ulaşmanın şiddetli çatışkıları da siyasal olduğu kadar kültürel karşıtların ve öncülerin ortaya çıkması için zemin hazırlamıştı.

Bu sanatçılar, sanatçı ve toplum arasındaki ilişkiyi sorgulamaya ve aşırı sol ile aşırı sağ arasındaki ideolojik kutuplaşmaların ve üniter devlet kapitalizminin ortamında sanat yapıtlarının işlevi, kabul edilmesi ve algılanması incelemeye başladılar. Kendilerini eğitenlerin sanatının yalnız kendi toplumlarından değil, dış dünyadan da kopuk olduğunu fark ediyorlardı. O dış dünyada sanatçılar sanatı ve sanatın gerçek dünya ile ilişkisini sorguluyordu; gençler, o gerçek dünyanın da odaksızlaştığını, yapısöküme uğradığını ve farklılıkların belirginleştiğini seziyorlardı.Artık, 60’lı ve 70’li yılların Batı’lı ünlü sanatçılarının açtığı yollardan birini izlemek zorundaydılar.

Paradoksal olarak en uzak, ama aynı zamanda en yakın yollardan birisi, Kosuth’un yoluydu. Uzaktı, çünkü uygulamaya açık ve felsefi değilse bile kuramsal bir yönelimi vardı, ve bu da dilin kendisini bir model ve kaynak alan (Wittgenstein, Benjamin, Borges, Saussure) bir kuramlar karışımında temelleniyordu; bu özellik değil Türkiye’de, başlangıçta Batı’da bile iyi karşılanmamıştı. Öte yandan, herşey çok yakındı, çünkü Kosuth işaret ve dille uğraşıyordu, imge ve temsiliyetle değil! Türk sanatçıların ikonakıran bir geleneğe sahip oldukları ve hat’ın da en yüksek dışavurum gücü olduğu düşünülürse, bu onlar için bilinen bir sanat yapma yoluydu. Dahası, Kosuth sanatın nasıl işlediği ve işlev taşıdığı ve dolayısıyla sanatçının nasıl rol değiştirdiği konusunda sorular soran kişiydi. 70’li yılların sonundaki Türkiye’de bu değişimi gerçekleştirmek ve sanatçıyı yozlaşmış zevkten ve yıpranmış biçimciliğin modernist geleneğinden kurtarmak kaçınılmazdı. Daha sonra, yalıtılmışlıktan kurtulmak ve düşüncelerini iletmek için daha etkili yollar öğrenmek isteyen sanatçılar için Kosuth, sanatı diller ve kültürler arasında kullanarak, dildeki aynılığı ve aynı zamanda farklılığı işaret ederek yerine-özel ve kültürüne özel yapıtlarına başladığında, daha da önemli sayıldı.

Yaklaşık yirmi yıl, Kosuth sanatçıları uzaktan etkiledi. Güç olmasın da geç olsun, dityerek, Kosuth’u Istanbul’a çağırmayı ve Borusan Sanat Galerisi’nde çalışmasını sağlamayı, başardık. O, on günden kısa bir süre içinde, galerinin koridor biçimli mekanını, koyu gri duvarlara, çepeçevre dolaşan ve kadanslı bloklar olarak titizlikle yerleştirilen metinlerin katedraline dönüştürdü. Türkiye’ye göç etmiş, Türkiye’den göç etmiş felsefecilerin, sanatçıların ve aydınların adları da bu sözcükler yığılmasını taçlandırdı. Mekan bir parçalanma ve bir bütünleşmeyi aynı anda kucakladı; kuşkusuz bu belirgin ikilik, Kosuth’un amaçlarından birisidir.

Sıradan izleyici için, Kosuth’un sanatçı olarak yaptığı bu büyük katkı, “söz” zenginliğinin, “mekan” zenginliği ile birleşmesidir. İşin bu yönü bile, geleneksel dinsel mekanlardaki hat kutsal anlamları açılklayan “hat” zenginliğinin değerini bilen bu izleyiciye yabancı sayılmaz. İzleyici, yine farklı metinlerin çözümlendiğini, kimi parçaların seçildiğini, parçalar arasında bağıntılr saptandığını ve ortaya çıkan kavramsal görüngünün sanatçı tarafından bulgulanmış bütüncül bir sistemde denetlendiğini anlayacak ve algılayacaktır. Yapıt bütün bu asalarla donatılmış olarak, modernist bakışı ve onu çerçeveleyen ideolojileri yerinden oynatır.

Koosuth’un, galerinin ikinci katında sergilenen önaraştırmaları, yeni dilsel ve ideolojil kuramların modernismin temel savlarına saldırılan, modern felsefenin yapı söküme oğratıldığı, farklılıkların birlikler ve kimliklerin önüne geçtiği, odakçı ve yetkeci anlamın bırakıldığı ve yokedildiği 60’lı yılların siyasal, toplumsal ve kültürel ortamında temel taşlarıydı. Batı-dışı dünya için bu değişiklikler henüz bilinmeyendi ve yabancıydı, yine de o zaman bile Kosuth’un işi burada coşku ve enerji uyandırdı. Çünkü bu işler bir sil baştan öneriyor, yeni bir düzen sözü veriyor ve gerçek yaratıcılık süreçlerini araştırıyordu. 90’lı yılların küresel kültür söyleminde büyük önemi olan bütüncül araştırmalarına gelince, Batı-dışının küresel ortamda kendi karar verici durumu ve işlevinin farkında olması dolayısıyla, bunların zorlanmadan algılandığı ve kabul edildiği, görülür. Yapıtının metinler-arası olması her türlü ruhsal ve anlaksal bağımsızlığa umut verir ve özgürlük tanırken, yapıtının gösterildiği ülkenin dilinde çalışmakta ısrarlı olması, ona, küreselliğin hakiki kurallarına göre, soylu bir davranış sayılan kolonyalist olmama ününü sağlamıştır.

Bu proje için seçtiği metinlerinde kendine özgü örgülü bir ussallığı vardır, ama yerleştirme yine de değişik tarihsel gerçeklere gönderme yapar. Birincisi, 1992’de, Linz’de Yabancı/Konuk başlıklı grup sergisine katıldığından bu yana gelişmekte olan bir yapıt külliyesine ilişkindir. 1993’de Venedik Bienali’ndeki “Bilinen Dünyanın Eşiğindeki Zeno” başlıklı ve Como’daki “Kurallar ve Anlamlar” başlıklı yerleştirmeler, Oslo’daki, Kunsthernes Hus’da ve Frankfurt’daki Schirnhalle’deki “Konuklar ve Yabancılar”ın arka tabanını oluşturdu.

Borusan Sanat Galerisinin, yüzyılın başında Ermeniler, Rumlar, Yahudiler gibi azınlıkların ve Rus göçmenlerinin yaşadığı, yabancı elçilikleriiin saraylarını kurdukları yer olan Beyoğlu bölgesinde olması, bu yerleştirme için mükemmel bir ortamdır. 50’lerden sonra bu bölgede köktenci değişimler oldu. Neo-klasik ve art-nouveau mimarinin sahipleri olanlar birer birer Türkiye’den ABD ve Avrupa’ya göçtüler ve o zamandan bu yana Anadolu’nun uzak köylerinden gelen yeni sakinler, kırsal kültürleriyle beyoğlu kültüründen arta kalanları bireştirmeye çalışıyor.

Ne ki, 90’lı yılların başından bu yana ana caddenin yüzü yıkımdan onarıma, tüketimden kültüre doğru değişiyor. Filarmonik orkestraya sahip olan Borusan Kültür Merkezi, sanat galerisi, müzik kitaplığı ile Türkiye kültürüne büyük bir yatırım oluşturmaktadır. Borusan Kültür merkezi’nin ana etkinliğinin müzik olduğu düşünülürse, Rossini ile temsil edilerek, Kosuth’un ıstanbul’daki yerleştirmesinin çekirdeğini oluşturdu. Yine, Rossini’nin ortaya çıkışı rastlantısal değil. Goethe’nin İtalya Yolculuğu, Rossiiini’nin İtalya’da Türk operası, işlevsel ögelerin zincirini bağlayan iki halkadır. Duvarlar boyunca ilerleyen ufuk çizgisinin üstüne yerleştirilmiş olan librettoda Türk sözcüğü, Türkler’in İtalya’da konuk ve yabancı olarak ikilemli durumlarını belirterek durmadan yinelenir.

Seçtiği karmaşıkmetinlere bakarak, Kosuth’un kendini yüksek bir bir toplum filozofluğuna konumlandırdığı sanılabilir. Hayır, o izleyici ile arasına böyle bir uzaklık koymuyor. Yapıtının kurulmasını denetlerken çalışmasını izlediğimizde, onun aynı zamanda bütün gazetecilerin sorularına yürekten yanıtlar yetiştirdiğini de gördük ve onun konuk sanatçı olduğu bu ülke hakkında derin düşüncelere sahip olduğuna tanık olduk. Anladık ki, metinlerin bireşimi, bu iş dizisine başladığından bu yana kurduğu söylemden daha fazlasını kucaklıyor, Türkiye’nin siyasal, toplumsal, kültürel düzlemini ve yaşadığı ikilemlerine karşı duyduğu ilgiyi ve anlayışı da… Yerleştirmenin kurulduğu günler boyunca, sanat üretimi deneyiminin gizemleştirilmesi ve manipüle edilmesi gibi durumlara açıkça karşı koyuyordu. Türkiye’de mütevazi sanatçılar büyük saygı görür. Bu bağlamda Goethe’den seçtiği ve Doğu felsefesinin esintilerini taşıyan şu sözler de rastlantısal değildir:” ‘Öl ve değiş’ i kavradığın zaman, bu zavallı toprak üstünde bir konuk olacaksın.

Beral Madra