Central Asia Pavilion in the 53 rd International Art Exhibition la Biennale di Venezia

4 June-22 November 2009

Ermek Jaenisch, Jamshed Kholikov, Oksana Shatalova, Anzor Salidjanov, Yelena Vorobyeva &Viktor Vorobyev.

Central Asia Countries (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan)

curated by Beral Madra

in collaboration with the commissioner Vittorio Urbani (Nuova Icona, Venice)

Nazira Alymbaeva (Kyrgyzstan) as assistant curator.

MAKING INTERSTICES

Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan in Central Asia are the geographical, socio-political and cultural background of this exhibition in the 53rd International Art Exhibition at Venice Biennale. At first sight, it may seem that my curatorial role in this exhibition, as a curator from Turkey, is based on an underlying cultural kinship between the Central Asian countries and Turkey. I wish this was the case.

Unfortunately, the cultural exchanges between Turkey and the Central Asian countries have been rather limited and marked by gaps and discontinuities. In fact, reluctance still prevails in the area of multilateral cultural relations. After the end of the cold war, Turkey, rather than pursuing some form of genuine and thorough engagement in the cultural field, opted for mobilizing the long-dormant pan-Turkism as an artificial lure in order to bolster her prospects in the possible business opportunities in the region. Even though the possible resonance of pan-Turkic identity in the region was vastly overestimated, these keen “world makers” did not hesitate to create, enforce, or promote it. The historical and cultural affinity and the language compatibilities were instrumentalized as a pragmatic tool for better business.

Regretfully, we have failed to construct an earnest and productive artistic and cultural exchange throughout the past decade and half. Perhaps, the geographical distance was too much for the commonalities to facilitate communication. Without doubt, it is necessary to steer away from romanticising the ethnic and linguistic commonalities. In fact, there is a reason why the contemporary cultural exchange between Turkey and the Central Asian countries continues to be minimal and the Turkish language with its different dialects have failed (and continues to fail) in bringing the Turkish and Central Asian intellectuals and artists together. To begin with, Central Asian communities experienced the Soviet modernism in Russian, not Turkish. And today, English is fast replacing Russian as the lingua-franca of the region. In short, while my involvement in this exhibition essentially aims to serve these art scenes in a professional way, I also hope that it might enable us to construct from ground up new lines of cultural engagement, in the form of reciprocal collaboration in contemporary art.

In many cases, the artistic choice and content of a country’s pavilion at the Venice Biennale, due to its inevitable financial grandeur and publicity potential, emerges as an outcome of a complex negotiation between the public institutions and the private sector. While, it is possible that artworks may reflect the socio-political or cultural background of the artists or articulate a statement or a commentary on the global state of affairs, we have also seen numerous examples of minimalist and abstract works that enticed the sophisticated cultural experts and the biennial audience. Nevertheless, it seems to me that the most lasting impression radiates from the attitude of the artist and from the concept of the artwork when it takes a position in relation to the Venice Biennale within the socio-politicaleconomical milieu of that particular era.

As the number of participating countries grew, their geographical distance became vast. Venice Biennale, being the oldest and the most desired meeting place for those who produce and trade in mainstream contemporary art, remains to be the centre. Indeed, it has modified its infrastructure in order to include the margins and the marginalized communities of global art production into its pool of diversity. Here, the desire mobilized by the lure of diversity and the anxiety emanating from the increasing cultural heterogeneity create an ambiguous coupling. The biennial system in general – continuously subjected to subversive criticism – requires an intercultural exchange 0f artists as well as curators. The artists have willingly embraced a self-induced nomadism in order to follow up the emerging agendas and trends in contemporary art, hoping to benefit from the possible face-to-face encounters with the Other culture – even if the Other culture has already been over-determined by the impositions of the global economy and in reality do not radically differ from the self in its everyday concerns. For curators this expansion opens two fields with contradictory characters: on the one hand, it is a new and promising field of knowledge and experience and on the other hand, it is a new job market that may have even more dramatic conditions than the market in her country or region of origin. The pathway that separates the field of knowledge and the market may be paved with glittering as well as slippery stones. The discrepancy between the socio-political background of the curator and the new field of operation determines the nature of the position and the task of the curator. Thus the process of democratisation, the development of a neoliberal capitalism, and the structuring and transformation of the culture industry are key issues in producing and organising exhibitions and bringing them into the mainstream. The conditions of production undoubtedly shape not only the content of the art, but also the aesthetic approach and achievement of the artists as well as the curator. The priorities of art making in former Third World or post-Soviet contexts are the opening of expression of individual creativity, the commitment for addressing the social and cultural transformations, the quest for reciprocity, and the construction of forums for cultural and artistic discourse. For curators working in these environments, curating becomes a rather complex task that involves engaging in socio-political debates and criticism that take place artistic circles – in many cases taking sides with certain groups of artists – and counterbalancing the ever present competitive conditions of the new global art order with the indispensable but long-ago forgotten solidarity practices. These are some of the questions concerning the position of the curator that needs to be asked when it comes to distinguish the traditional, constitutive, and economic facts and figures in the global diversity.

The motivations of artists in the post-national, post- Soviet, post-9/11 context seem similar to that of the curator; for they also position themselves on the borders of a sophisticated and complex culture industry which is shaped by a network of corporate art institutions, collectors, dealers, and galleries. Through this rather restricted position, they pave their way towards free thinking and expression and strive to improve the quality of communication between the local, regional, and global artistic practices and theoretical discourses.

In the case of Central Asian artists, the 60 years of rupture between the traditional or indigenous cultures – which are now highly esteemed – and the Soviet culture is an essential field of research and careful scrutiny. Without doubt, these fundamental rupture needs a sustained effort and thorough-going planning to be transformed into effective artworks – not only because of the failing facilities and infrastructures, but also because of the modernist nature of general public appreciation contemporary art that consigns these artworks somewhere between handicraft and decoration. Photography and video, the most commonly used tools of contemporary art practices are the two techniques that gave the artists the upper hand in breaking through this prejudice. In the eyes of the public, these techniques elevate contemporary art making to an intellectual endeavour. These challenges unquestionably go beyond the tasks and efforts of artists who live and practice in countries with already fortified and established official and private cultural policies. On the other hand, it might be a mistake to consider their context only as a disadvantage. It is true that these artists are caught between the traditional ethnic heritage and the nationalist and religiously conservative socialist realist cultural discourses and practices. Oddly enough, all these retrospective fields of influence provide a vast pool of visual, verbal and documentary material that can be used, recycled or re-evaluated within the multifarious technologies, strategies, and methodologies of contemporary art making and circulation.

Throughout the Cold War, the lack of cultural relations and inhibition of communication disconnected the Central Asian art scenes from the centres of different modernisms, extinguishing the universalistic and at times homogeneity-inducing impulses of Western modernism.

The recuperation of these lost times are now conveyed through the works of art that consciously refer to the recent past… Here, the ambiguous character of these products of visual art practices should be assessed with respect to their influence on the different communities of a country. In most cases, even when the artists insert a familiar traditional material to their transgressive presentations in order to ignite awareness or an alternative perspective, these communities continues to remain distant and disengaged even to the indirect implications of these simulations.

According to experts, the manner in which the driving force of globalisation manifests itself in the Central Asian context follows a familiar path: Revitalization of nationalist ideologies combined with a neoliberal economic fundamentalism. Neoliberal ideology does not only fuel the commodity trade and the construction boom, but also the trafficking of people and the emigration for jobs. Most of these forces are identified and critically commented on in the semi-documentary micro narratives that uses photography and video as their mediums. The impact of the Soviet period on the cultural life of the Asian continent, usually referred to as Sovietization, figures in most of the works as a common historical heritage to be re-inspected, questioned, and finally disdained, in a transgressive and humorous manner that mobilizes the language of surrealism.

Another common strategy is to accentuate the traditional and geographical cultural particularities using the discourse and techniques of contemporary art: semidocumentary video works, photographic series, and installations with traditional artefacts are used to re-stage this uncanny encounter between the traditional content and the contemporary form.

It is necessarily impossible to provide a definitive panorama of the evolution of any art scene – even if it is useful to attempt at one only to come up with some new strategies for moving forward. In the case of Central Asian artists, we can locate the emergence of contemporary art making in the mid-1990s. First notable exhibitions were realized in Bishkek, Tashkent, and Almaty between 1997 and 2000. An important publication that documents the emergence of contemporary art is Art Discourse-97, a volume edited by Valeria Ibraeva on the occasion of a seminar on the contemporary art theory and practices in Almaty (28.08-01.09.1997). Many of the participating artists that were featured in this volume were also able to participate in the 51st and 52nd Venice Biennales as well in group shows that travelled a number European capitals.

For instance, while Yelena Vorobyeva and Viktor Vorobyev (Kazakhstan) participating in the 6th Istanbul Biennial (1999), Alexander Ugay and Roman Maskalev (Kazakhstan) participated in the 9th (2005). Throughout Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan were invited to European centres under the title “Contemporary Art from ” curated by Andrea Dietrich in Weimar (2001); “No Man’s Land” in House of World Cultures in Berlin (2002); “Trans-forma” curated by Daniela Gruninger and Valeria Ibraeva at Geneva Contemporary Art Centre (2002); “From Red Star to Blue Dome” at the Islamic Worlds, IFA Gallery in Berlin (2004); “Cultural Heritage of Central Asia” at the UNESCO Headquarters in Paris (2006); “Contemporary Art from Central Asia” at the Uazdovski Palace in Warsaw (2006); “Peace Rose” at the Spiridonov House in Moscow (2006). Participations in the exhibitions like “Destination Asia: Flying over Stereotypes” in Mumbai, “Paradoxes of Polarity” curated by Leeza Ahmedy at Bose Pacia Gallery in New York, 2nd Moscow Biennial, 1st Contemporary Art Biennial in Thessaloniki, “Time of Story Tellers” at Kiasma in Helsinki; “Thermocline” at ZKM in Karlsruhe, and “Turbulence” at the 3rd Oakland Triennial in New Zealand shows the intensified involvement of Central Asian artists and art experts in international networking.

Looking at these titles, one cannot help but think that the inquisitive gaze of European art centres demand a particular type of discourse. The expectations of these mainstream institutions and experts, somehow still reproducing a subtle kind of Orientalism, have been answered with these titles; mockingly attract attention, but concealing some vicious surprises. This period is now over and it is time for reciprocity.

All across the non-Western world, the change is very much related to the quantity and quality of contemporary art productions, including critical theory and visual culture, that gradually replace the notion of the so-called fine arts and of the socio-political and ideological alterations these productions implant into the epistemology of these societies. The most solid factor, namely the ideology of the nation-state is still retaining its power, but it is becoming more and more in tune with the permissiveness of neoliberalism. In this new context, micro-political concerns of local and marginal cultures unexpectedly float up, manifesting their differences. These changes are reflected in artworks in the form of free and unrestricted declarations of individual statements that address micro as well as macro concerns.

Many of these works are far from being hermetic and metaphorical; they are mostly sociological and based on documentation. One can even say that art making has transformed into a tool for articulating a neo-anarchist attitude. Evidently, this attitude (favoured in the mainstream art scenes as democratic manifestations of non-Western societies) owes its force not only to the political engagement of the artists but also to the freedom afforded to them due to the absence of the oppressive international market interests and conceited collectors in the region.

The dissident individual, the contemporary artist of the emerging or developing democracies all over the Middle East and Central Asia utilize art making in order to gain a visible presence within the socio-political horizon of his/her territory. However, this horizon is on the one hand shadowed by the politicians and bureaucrats and on the other hand by the business people who have the financial resources but in general are not so interested in contemporary arts. A third shadow is cast by the media and the advertisement culture which is extremely influential in manipulating the public opinion; every cultural event has to make itself visible in the billboards and the television, otherwise it is too small to be seen…

The title “Making Worlds” is full of hope. It invokes the utopian image of the “modernist innocence” of the artist. This image has long been shattered under the pressure and the manipulations of the cold and calculative logic of the now dominant neoliberal economism. Under neoliberalism, the artist is transformed into an entrepreneur conjuring all kinds of strategies in order to be visible just for a few minutes. At some level, it is a truism to assert that the artist is an individual who has the ability to change the world. But perhaps, we can be a bit more cautious and suggest that an artist is an individual who can still believe that s/he can change the world. Indeed, we unconsciously believe that art has changed the world even if we acknowledge that it has not changed the world in noticeably different ways than anything else.

Throughout the last century, the world has changed many times, radically transforming the lives of the communities and individuals, brutally erasing the historical and cultural memory, sweeping away the utopias of many generations. What was the function of the artists throughout these political and economic turbulences? Jacques Rancière notes that “Responsibility and commitment were not categories of art, only the artist is committed as a person.” (1) Indeed, contemporary

artists of the globalised world are committed; with their works that articulate theory with practice, they provoke the intellectuals and the public to re-think on how to make worlds that are worth living. This attitude resonates strongly in the words of Foucault: “Intellectuals are themselves agents of this system of power – the idea of their responsibility for ‘consciousness’ and discourse forms part of the system.

The intellectual’s role is no longer to place himself ‘somewhat ahead and to the side’ in order to express the stifled truth of the collectivity; rather, it is to struggle against the forms of power that transform him into its object and instrument in the sphere of ‘knowledge,’ ‘truth,’ ‘consciousness,’ and ‘discourse’.

How should we evaluate the position and behaviour of intellectuals, academicians and artists working and producing in the macro political environment of Turkey, South Caucasus, Middle East and Central Asia? The most convincing elucidation can be found in Deleuze’s arguments. Deleuze has used in many of his texts the biological term “vacuole” (transl. interstices) as a metaphor. Vacuoles are empty cell compartments which are filled with water containing inorganic and organic molecules. Deleuze proposes these little gaps as places of silence and solititude within the turmoil of neoliberal politics and economies. He says: “What a relief to have nothing to say, the right to say nothing, because only then is there a chance of framing the rare, and ever rarer, thing that might be worth saying.”(2)

Here, the condition of non-communication in these interstices serves as an escape from the dominant forms of political and economic power. It appears that the contemporary art productions and their creators have no significant location and position in the political, economic, official and social priorities in the above mentioned territories. In this ambiguity of existing and non-existing, these art scenes resemble interstices of noncommunication.

However, they evidently breed alternative spaces in these societies. The current emergence of individual attempts to communicate with prospective international partners and group initiatives is a phenomenon that can implant a new dialogue between the society and the state. The artists operate to create prolific nucleus of free thought and expression, suggest inconspicuous or minute verbal or visual models of resistance and a silently influence the younger generations

in these territories. Making Interstices proposes to recognize the intricate distinctions and options of art making in the multiplicity of the global world. If Making Worlds presents the broadspectrum and process of today’s art, Making Interstices indicates the way artists work, operate and produce in Central Asian countries – and many other countries that have similar tensions between the recent past and the present, i.e. throughout the political and economic turbulences of the last thirty years. Violent complications of rapid ideological and governmental transformations aggravated the artists’ ability to discover, to employ and to exploit the little gaps (interstices) between the conventional and most of the time oppressive macro politics and economy. Making Interstices is a strategy that allows the artist to configure his/her thoughts, desires and humour freely into a tactical, experimental and exploratory intervention through art…

The works of the six artists presented at the Central Asia Pavilion in the 53rd International Art Exhibition at Venice Biennale will illustrate the latest directions in the art making in consideration to the above described sociopolitical and cultural background. No doubt, contemporary art in Central Asia is not limited to this exhibition. Here, the focus is on the continuous intensity of the production, on the obliqueness of the vocabulary of forms and concepts and on the significance of the attempts to combine different realms. These are the realm of the culture industry in transition, the realm of the higher intellectual level of human activity and the realm of the creative individual as a transmitter and as a critic, both to his space and to the global culture industry sanctions.

Ermek Jaenisch’s two recent works, False Fabrics of the World, a photo series, and Blink of Autumn, a video, reveal two aspects of his culture, namely the fact that this culture is now judged on its historical image and the disparity of urban and rural contexts. The photo series show monument like constructions that are created as an accumulation of historical objects, symbols and signs and placed in a rural background. Here again we acknowledge the artist’s humorous approach to his cultural heritage and to its reception and recognition by the Western gaze. At

first sight, these monuments look easy to construct and it seems that it would be easy to find a public that can appreciate them as they embody an eclecticism of the zero point of contemporary culture, as Lyotard (4) has formulated it. Yet they also show how weak, simple, and ultimately conquerable the local cultures are and how they are constructed as exotic and bizarre objects of a spectacle.

The video is a restless comment on the alienation between the urban and rural environment of the artist’s city (Bishkek). A spoon dangerously balanced on the rim of a turning soup bowl, symbolizing the local economy and daily life, marks the fragility of the present order. The video playfully intends to show the affirmation of the power of globalisation over the existing order. Here again Jaenisch combines different ways of catching the attention of the viewer; the tension of speed, as experienced in fiction films and the transgressive gaze that gives the viewer his own interpretation on the consequences of globalisation.

With two recent video works, Jamshed Kholikov is searching for answers to questions “Who are we?”, “Why are we here?” and “What to do?”. In all probability, these questions are frequently being asked by many others who find themselves within the current global political order. Kholikov looks for the last traces of the past order and even if the works that generate out of his discoveries are quite familiar in concept and execution, they present this common predicament in his geography. Kholikov’s Bus Stops is an ambitious voyage in a vast geography covering

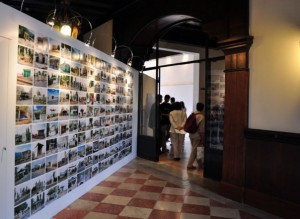

Bishkek, Hisor, Istrashan, Khojent, Pamir, and Uzbekistan as well as a voyage to the triviality of derivative architecture and design. Photos of almost 200 bus stops, which are practically the idea of the historical, traditional and ideological monument, reveal a local artisanship and folkloric aesthetic which in many examples map the ideological transformations from the concrete shelters adorned with Soviet symbols to unbreakable glass-boxes for the advertisements of an emerging neoliberal market economy. He bestows these bus stops with another function; for Kholikov they are like stops in our voyage from birth to death that gives opportunity to pause and think. They are the beginning and the end of our trips, our wasted hopes and wasted illusions and they are the stops when people ask themselves the well-known post-Soviet question: “What to do now?” Anzor Salidjanov’s pictures are anchored in the history of art. We know that photography is the most effective way 0f reworking the modes and compositions of traditional painting. Salidjanov’s pictures humorously fuse the memory of the traditional painting with local memory. The native population re-places the figures of the traditional painting creating an ironic anachronism; however he calls back the viewer to contemporary reality by placing himself – as a rather cynically contented individual – into the centre of the pictorial event. This is a transformation and displacement that helps the viewer to read the conditions of the present against the context of the history of art. In Salidjanov’s works Western art historical images are being used as the standard field of knowledge to convince the intellectuals and art public. This tool gives Salidjanov the possibility to convey his reading of art history within his own cultural context.

Through these grand narratives, represented in these traditional compositions, Salidjanov gives the ciphers of today’s distress of geographical, social, cultural realities in his geography and culture. At first sight these are amusing images, heightened for example by the witty presence of the artist himself; yet the message is as serious as exploiting the almost sacred paintings of the Western culture. It is not that art history haunts the Uzbek contemporary art scene. The message focuses on the constructed cultural identities that serve as tools of determining the deep seated cultural difference; or the difference as seen by the Western gaze. Edward Said’s argument orientalisation is not so much about the Orient as it is about constructing an identity for European cultures to contrast themselves against is to be remembered here.(5) Salidjanov invites the viewer to construct an identity of Asian cultures against the grand images of the West.

Oksana Shatalova’s performance based two recent video works, Open Air Tango and Red Flag pleases the viewer’s spirit with their enjoyable, amusing, and ironical atmosphere before it creates an ambiguity that at once confirms our cliché knowledge of the post-Soviet past. The ludicrousness of the dedication to the red flag and the absurdity of the tango in No Man’s Land divert the viewer to place direct references to her socio-political background. The associative elements to the past are

juxtaposed with the new possibility of freedom to be allternative and with the intimate world of feminine experience. The universal language and inspirations of tango and the nostalgic Soviet girl song (singer Arkady Severny [1977]) are in discursive exchange with the stereotypical images. In Palazzo Molin, Shatalova’s SPAsilk- milk-mysterious life performance is exhibited in six photos and as video screening. It is a performance documentation that pleases the viewer’s eye and spirit

with their enjoyable, amusing and ironical images; but raises questions about the usage of milk, that apparently is the symbol of “organic life”, “power of nature” and “affluence” in Central Asia. Her performances visually reflect a subtle way of expressing the absurdity of contemporary life. However, content-wise her works challenge the viewer through mobilizing a selfidentification as a female located within the new order of art but stuck in a fractured moment between the past and the future. Yelena Vorobyeva and Viktor Vorobyev work together since the beginning of 1990s and have contributed to the contemporary art scene in Kazakhstan with their multidisciplinary works; photography based on research and discovery, drawings, sculptures, videos, and installations. The biennial audience will remember their installation “Kazakhstan: Blue period”, 2002-2005, with 138 color photos. One of Vorobyevs’ more recent works is a poetical and philosophical survey of day and night, conceived as an installation of wall texts, drawings, and video. Yelena Vorobyeva claims: Only our silly confidence that the Sun will always rise at its appointed time and will not crash down on us at its zenith saves us from getting crazy and nostalgic. Its appearance is as exciting as a real show; its disappearance reconciles us with the temporary loss. Two videos showing still life during day and night might be interpreted as a real-time documentation of a simple detail of daily life, quite far from Europe, where it will be viewed by remote and unknown audiences. Or it can be received as a metaphor for the reality that “making worlds” is at the end bound up with the laws of nature. The installation Day-Night & Artist Asleep is an environmental tableau of a poetical still life video and a sleeping artist; when he wakes up he will be Making Masterpieces…

Beral Madra, December 2008 – April 2009

Notes

1 Fiks, Yevgeniy and Olga Kopenkina, “Legally Soviet: A

Conversation”, Rethinking Marxism, Volume 20, Number 3, July 2008,

p. 431.

2 “Intellectuals & Power: A conversation between Michel Foucault

and Gilles Deleuze”, http://libcom.org/library/intellectuals-power-aconversation-

between-michel-foucault-and-gilles-deleuze.

3 “Le couple déborde” in a short essay in Pourparlers, from Macropolitics:

Politics After Poststructuralism, Raymond van de Wiel, Research

Jury Presentation, April 27, 2007, http://www.raymondvandewiel.org

/macropolitics.pdf and Deleuze, “Mediators”, Negotiations, 1972-1990,

trans. by Martin Joughin (New York: Columbia University Press,

1995), pp. 121-134 (especially p. 129).

4 Lyotard, Jean-François, “Was ist Postmoderne?”, Postmoderne und

Dekonstruktion, Stuttgart, Reclam, 1990, p. 40.

5 Said, Edward, “Introduction”, Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the

Orient, Harmondsworth, Penguin Books, 1995, pp. 1-28.13