KAVRAMSAL BİR MİRAS: Öncü Yerleştirmeler

A CONCEPTUAL HERITAGE: Vanguard Installations

15 EYLÜL/SEPTEMBER-14 EKİM /OCTOBER 2011

AÇILIŞ/ OPENING: 14 EYLÜL /SEPTEMBER

ERDAĞ AKSEL, CANAN BEYKAL, SELIM BIRSEL, AYŞE ERKMEN, AHMET ÖKTEM, SERHAT KIRAZ

Küratör/Curator: BERAL MADRA

Küratör Asistanı/ Asistant to the curator: Hande Taş

sergi yeri/exhibition venue

ARTAM GLOBAL ART SERGİ SALONU/EXHIBITION HALL

Bu sergi ANTİK A.Ş. ARTAM GLOBAL ART ORGANİZASYON tarafından gerçekleştirilmiştir.

This exhibition has been realized by ANTİK A.Ş. ARTAM GLOBAL ART ORGANİZASYON

Basın Bülteni

12. İSTANBUL BİENALİ dolayısıyla bir paralel etkinlik olarak Artam Global Art Sergi Salonu’nda gerçekleştirilen bu sergi, 1970’lerde sanat üretim alanında gerçekleşen değişimi ve 1980’lerde somutlaşan bir yapıt üretim birikimini kavramsal bir miras olarak nitelendirerek gündeme getiriyor.

Erdağ Aksel, Canan Beykal, Selim Birsel, Ayşe Erkmen, Ahmet Öktem, Serhat Kiraz’ın sergide sunulan bir dizi yapıtı, bu mirasın zamanın ve koşulların izin verdiği ölçüde korunabilmiş olan bir bölümüdür. Bu dönemdeki üretim sanat metinlerinde ve eleştirilerinde Batı odaklı sanat tarihi bağlamında geçerli olan “Öncü Sanat”, “Kavramsal Sanat”, “Post-kavramsal Sanat”, “Yerleştirme Sanatı” gibi başlıklarla anılmıştır.

Sergi,

-Küresel kültür sanayi bağlamında yaratıcılık süreçlerinin temellenmesi ve belgelenmesinde önemli bir yeri olan “çağdaş sanat müzesi” olgusu içinde bu üretimin gösterilmesinin gerekliliğini vurgulamak için bir model oluşturmak,

– Bu mirasın üretimini sağlayan düşünce aşamaları ve örgüsünün o dönemin siyasal, toplumsal, ekonomik koşulları anımsandığında, yol gösterici, yapıcı ve açılımcı olduğunu ve Türkiye’nin demokratikleşme sürecine önemli bir katkıda bulunduğunu anımsatmak,

– Modernist resmi kültür politikası ve resmi sanat görüşü ve toplumsal kültür mutabakatları dışında gerçekleşen bir üretiminin toplumun sanatı görme ve algılama biçimini ve sanatın statüsünü nasıl değiştirmeye çalıştığını izletmek,

– 1960-1990 arasında Avrupa ve ABD’de gerçekleştiği varsayılan Modernist kırılma ve Post-modern üretim sürecinin gerçekte Sovyetler Birliği ülkeleri, Balkan ülkeleri ve Türkiye’de aynı zamanda ve koşut içerik, biçim ve estetik değerlerle yaşandığını göstermek, amaçlarını taşıyor.

12. İstanbul Bienali dolayısıyla İstanbul’a gelmesi beklenen uluslararası sanat sanatçılar, sanat uzmanları, galericiler ve koleksiyoncular Türkiye’nin günümüzdeki sanat üretiminin belleğini oluşturan bu başlangıç sürecini ve üretimini tanımak ve incelemek olanağını bulacaklar.

Catalogue Text

A CONCEPTUAL HERITAGE: VAUNGARD INSTALLATIONS

A Retrospective Exhibition On The Works Of Erdağ Aksel, Canan Beykal, Selim Birsel, Ayşe Erkmen, Ahmet Öktem and Serhat Kiraz

“A Conceptual Heritage: Vaungard Instalations” exhibition revives and draws focus to the transformation that took place in the field of artistic production in the 1970s and an accumulation of works that became consolidated in the 1980s by defining these as a conceptual heritage. No doubt the series of works presented in this exhibition constitute only a part of this heritage; or rather, they form a part of the production that was possible to preserve as far as time and conditions have permitted. In texts of art history and criticism, the artistic output that took place during this period has been referred to as “Pioneering Art”, “Conceptual Art”, “Post-conceptual Art” and “Installation Art”, titles that enjoy certain validity in the context of Western art historical terminology.

This exhibition has a retrospective quality, however this artistic production that in a general sense points towards the transition period from Modernism to Post-modernism, is not presented as a process that has run its course. This particular type of art, that first surfaced in the world in the 1960s, and emerged in Turkey on time and without delay, has not come full circle yet; diversifying and acquiring new openings, it continues to this day.

This heritage is composed of artworks; however, the stages of thought and map of ideas that made the production of these artworks possible is, in my opinion, much more important than the exhibited ones; we can comprehend how instructive, constructive and innovative this train of thought has been only if we recall the political, social and economic conditions of the period in which these artworks were produced.

There is no doubt that human production that manages to surpass conventional forms of thought limited by the political, social and economic conditions of the time, and proposes a new idea and a new way of thinking carries a certain value; such ideas and thoughts are recognized as cultural productions not only within the locality they were produced, but in a global context. The qualities of such cultural heritage relevant to this exhibition are described by Wikipedia as “they are the products of creative human genius; they reveal the significant interaction between human values during a certain period or at a specific cultural location; they are witness to a particular cultural tradition; they are directly or materially linked to ideas, beliefs or artistic and literary works”.

The works in this exhibition are examples that represent a heritage of this kind; they reveal the direction art will take beyond that point in the period they were produced, they possess qualities that connect the local to the international environment; they reveal the unfolding of intellectual processes on the path towards democratization. It may be considered an exaggeration to ascribe these sublime to some ten or twelve works presented in this exhibition; however, since this is a case of presenting representative samples, it would seem appropriate to refer to these qualities as such.

Turkey expresses pride of its historical heritage in the context of its official cultural policy, yet it is not a country that has succeeded in preserving its 20th century Modernist and Post-modernist heritage! Or rather, that cultural output produced in Turkey during the 20th century which has universal qualities has not been, or cannot adequately be acknowledged as part of the cultural heritage that needs to be preserved. Due to a number of unresolved issues on an epistemological, political and socio-psychological basis, Turkey has failed to museumize and present its architecture, visual and aural arts in a way that wider masses can view, research and interpret them. The structure to present this heritage in conformity with the presentation criteria of the contemporary art object, within post-modern museology standards, and the critical framework set forth by global discourses of culture does not exist. Cultural works in the hands of the state, in private and individual museum initiatives and in private collections behind closed doors remain secret, awaiting as reinterpretation material. As the 20th century rapidly recedes in the rear-view mirror, this heritage we leave behind and remains concealed and/or beyond public access, or can only be shown in parts and out of context; casts a shadow of obscurity over the background of 21st century cultural productions and creates an epistemological void for future generations.

This exhibition can only present a selection of the works of six artists from the 1980-1995 periods. Therefore, this text will endeavour to explain why these works are part of our cultural heritage. To do this, we must first and foremost recall the period in which these works were produced and the political, social and cultural circumstances of that period. Secondly, it is necessary to touch upon artistic production in this period, both in and around Turkey and centred in Europe and the US. Finally, it is necessary to explain the ratio legis behind these works and the forms through which they represent it.

1.

All the works included in this exhibition were produced in Istanbul; the reason in stating this is to emphasize the proven relationship between means, processes and the impact of artistic production and the urban environment. Since the 1980s, Istanbul has become prominent on the global scene, as a model city in terms of the complex symptoms and consequences of this relationship. Even though the general cultural policy of Turkey has still not been updated, and the delay in the transformation of modernist infrastructures into globalized infrastructures, a visual-aural artistic production that runs parallel to the political-social developments of recent history and its harmonization/dissonance to the neo-capitalist system does take place in Istanbul.

In the 1970s, European capitals gradually began to lose their position as centres in the imperialist context. Important reasons for this change include an intense flow of immigration that continued for a few generations from underdeveloped and authoritarian countries towards the cities of developed democracies and economies; increasingly ineffective Eurocentric discourses that were deconstructed by European theorists, and acceptance that a world art history written from a colonialist, orientalist and imperialist perspective had become obsolete. In this context, it is clear that the proliferation of the discourses of theorists such as Frantz Fanon, Homi K. Bhabha, Stuart Hill, Fredric Jameson and J. F. Lyotard initiated the debate around these issues. However, the widespread recognition and interpretation of these theorists amongst intellectuals in Turkey took place only by the end of the 1980s.

From 1960 on, Istanbul also experienced local immigration, and the population of the city grew as its borders rapidly expanded. As the transition from state capitalism to liberal capitalism became more acute in the mid-1980s, a consciousness of democratization was simultaneously stimulated. The growth in communication networks and the flow of information provoked a change in Istanbul towards a mega/metropolitan identity that strived to respond to political, economic and technological influences coming in from the West, that experienced the processes of modernism and post-modernism simultaneously, and that reflected the dilemmas of tradition and contemporaneity. Önerim buraya bütün kırsal kimlikler yerine İstanbul göçünü kapsayanları daha iyi belirtmek için “These” sözcüğünü eklemek Rural identities continue to enter into a process of urbanization, continuously changing places, intertwining with each other, and co-existing side by side.

Forfeiting its position as the focal point of the world in the 16th century with a decline that lasted several centuries, during the latter part of the 20th century Istanbul had to take its place within the global network of communication this time as one of the giant hubs, continuing to retain within itself this dilemma between the centre and the periphery.

Among identities of the centre and the periphery, the most striking qualities are that of being a “receiver” or “provider” of culture. During the period when it was a centre, or in other words when it was Byzantium, Constantinople and the Ottoman Istanbul, the city sustained an incredible balance and synthesis of these two conditions. In the 20th century, during the process of change in political, economic and social identities; this balance and synthesis broke down and the condition of the receiver prevailed. Subsequently, under the title of Westernization, the city experienced a process of internalizing modernism and universality. It is due to its status as a receiver that throughout the 20th century the city was considered to be on the periphery.

A threshold had to be crossed in order to pass from the stagnancy and insecurity brought on by the receivership of Modern art production – a period extending from the adoption of the perspective of the Renaissance as part of the Westernization program of the Ottoman Empire, to the D group – to becoming a provider within the new world order. This transition can also be explained in terms of discarding the formalist and internal modernist qualities of the work of art that is focusing on US critic Greenberg, and thereby entering into analytical or interconnected relationships with the political, social and cultural data of the period and place the work of art was produced in. Nilgün Özyaten, in her doctoral thesis on the 1965-1992 period of art in Turkey, states that this threshold was first challenged in the 1970s with attempts to “understand, interpret and examine contemporary art”. (2) As Istanbul’s attempts continued to complete this process and spontaneously establish a new balance and synthesis of receiver-providership; in the global environment, the phenomenon of cultural reception-provision formed a new balance and synthesis. This was not necessarily a situation that was expected and prepared for; official cultural policies remained alien to this development into the 2000s, whereas private sector cultural policies attuned themselves to this development much faster.

The foremost quality of Istanbul that enables it to become a giant-hub in response to global change is no doubt the fact that it carries the memory of an imperial centre that encompasses the culture of three continents, and the versatility provided by its geographical character. In addition to this, the cumulative experience derived from the integrated relationship with Europe which it has sustained since the 14th century also has significance. Both of these qualities continue to exist today.

Today, societies of consumption located on the global hubs that are undergoing the different stages of capitalist processes are experiencing either the creative outcomes or openings; or clashes, explosions and depressions of the encounter between local cultures and global mass culture. The literary, objective, visual and aural productions of this encounter are contemporary works of art that visually-intellectually enrich people, and enable the emancipation and democratization of societies. From this point of view, contemporary works of art serve to decipher the giant hubs of the global network of communication and exchange. These are global codes; however, by reading the formulae that set them up, we can access the basic signs and first examples, and gain an understanding of historical, traditional, social etc. characteristics of a local and regional nature.

Altan Gürman’s “Montage 5 and 6”, a work from 1967, and “Padded”, conceived in 1972 and realized in 1976, can be presented as examples of these first codes. These unusual object-paintings with schematic qualities and produced with unconventional synthetic materials, standardizes and presents a concept – bureaucracy – belonging to the current political system. This visual production is not narrative; it visualizes the concept. In the 1960s and 1970s, neither the art audience, nor intellectuals in other fields of art, nor the wider masses were part of a process that would enable them to comprehend and perceive these ciphers. The polarized movements of Early and Late Modernism proclaiming art for art’s sake or art for society’s sake and post-World War II movements of art in Europe and the USA such as Abstract Expressionism, Tachisme and Art Informel had lost nothing of their dominant influence in Turkey. The D Group’s and the Group of the New’s understanding of art, developed between 1933 and 1947, was based on Cubist and Constructivist concepts. It combined with Informel and Tachiste influences from Europe in 1949 and diversified under the non-figurative general heading.

In the 1960s and 1970s, plastic arts, to use the term of the period, were not a type of production definitive of Turkey’s cultural identity. It is true that modernist art and sculpture production failed to reach the wider masses and did not go beyond the field of interest of a small middle-class and intellectual section of society who knew the value of this branch of art in the international environment. Whereas sculpture, because of state commissions for monuments, continued its existence often with efforts to combine traditional elements with a geometric or expressionist abstract approach –damaging the value of sculptural production as a work of art. A field in which painting did achieve some success in reaching the masses was social realist painting, rendered with utmost faithfulness to reality.Türkçe metinde sol söylemler de var, önerim …reality and left wing discorses. However, this should not be confused with the US photorealism of the 1970s, because photorealism is also a narrative method created by communication media and mechanisms of consumption. The appreciation felt by the masses in Turkey for painting that resembled photography, on the other hand, was no doubt born out of the habit of interpreting art in a direct manner and the use of art for political ends. Developments in figurative painting in the 1970s also displayed efforts to break free of this framework and consequently there was an evolution towards a new expressionism. In the 1980s there emerged paintings with a critical realist and fantastic realist basis, which reflected a pluralist, liberal, individualist type of deformation and allegory. Research shall reveal that the appreciation and evaluation of these paintings also did not follow a smooth path.

In the context of the political and economic system of the time, it was in two respects that artistic production in the 1960s and 1970s had the appearance of late modernism in the third world. On the one hand, the modernism that was being practiced in line with the art for art’s sake view as required by capitalist discourse had become aesthetically stagnant; on the other hand, all the forms that abstract art allowed were being tried out with traditional, national and local values placed within them. Since there was no art market in Turkey during this period, artists were dependent on state institutions to maintain themselves.

Bize gönderdiğiniz metinde burada paragraf yapılmamış ancak İngilizce’de atlamışsız paragraf olmasını öneririm. The State Fine Arts Academy, an extension of the state’s art policy, and the School of Applied Fine Arts, based on the Bauhaus model, defined and supervised the art environment in Turkey, and art was the sole domain of these institutions. Those who remained outside of this domain had few options,

An important point that must be mentioned at this juncture is the existence of an artistic and cultural relationship, albeit restricted; between the Istanbul art environment and Western European countries. This relationship was limited to Germany, France, England and Italy who established cultural institutions such as the Goethe Institute, the British Council, the Italian Cultural Centre and the French Cultural Centre in foreign countries as part of their official cultural policies. Nevertheless, those who foresaw change and wanted to practice it tried to follow developments in the outer world.

It is evident that the Basic Education program, pioneered by Altan Gürman and added to the classical academic education curriculum contributed to the practices of 1980 generation artists. The main reason that impelled the founders of basic education towards change was no doubt the desire to rescue art from endlessly repeating itself under the influence of the expressionist, abstract and realist movements; and this could only be achieved by a rapid update. This became a breakthrough, however it is not possible to say that breakthroughs of similar vigour were carried out later when they were necessary. Under such circumstances, the Nouveau Realisme that Altan Gürman had adopted during his studies in Paris and began practising upon his return to Istanbul, or the other face of art, to use the term coined by the critic Pierre Restany, who contributed to the development of the New Realism in vogue in France during the same period, had to wait for the political and economic environment, society and individual citizens of Istanbul to pass through the necessary stages of capitalism. Although these obligatory stages of capitalism, in other words, the transition from early capitalism to capitalism proper and then on to the post-industrial period, were not internalized in an exact and complete fashion; after the irrepressible arrival of communication media and multinational consumption mechanisms in Turkey, this process of internalization became a thing of the past, as if it were done and dusted. The pioneering role in art during the contradictory and ambiguous decade of the 1960s belongs to the New Realist works of Altan Gürman that transform common objects into works of art, schematize militarism and bureaucracy and standardize traditional landscape painting. These are followed by Füsun Onur’s first installations formed with everyday objects and simple materials, integrating sculpture with time and space; and Şükrü Aysan’s works that use intellectual art against formalist art, and diverse types of languages, media and norms against traditional techniques of art. (3)

Works by a few artists that were precursors to change were supported by significant cultural activities focused around universities. The New Tendencies Exhibitions (1977-87) that began as a State Fine Arts Academy organization and continued under the supervision of Mimar Sinan University were realized to meet the need for the emergence of this new kind of production, its presentation to the wider masses and its articulation to international developments in art. Conferences and open forums held in this context (for instance, the Arts Towards the Year 2000 Symposium, 1977) contain declarations examining developments in contemporary art in Turkey within the framework of the educational system and culture industry. Works produced with techniques such as photography, text and printing; objects and installations formed with various industrial and everyday objects were prominent at the New Tendencies exhibitions. These exhibitions were discontinued with the organization of the 1st Istanbul Biennial in 1987; to a certain extent, the biennial assumed the role of these exhibitions.

The artists, on the other hand, laid the foundations of the artists’ initiative, the most valid and effective method of contemporary art production and distribution. The Art Definition Group, founded in 1978 by Şükrü Aysan, Serhat Kiraz, Ahmet Öktem and Avni Yamaner, was essential in creating the theoretical basis and the first examples of implementation applicable in this environment. From 1978 to 1981, this group organized three exhibitions, two of which were held at the Beyoğlu State Fine Arts Gallery, and in 1980 it published The Book as Art.

The A Cross-Section from Pioneering Turkish Art exhibitions (1984-1989) and the A, B, C, D Exhibitions (1989-1992) are important exhibitions in which this change was presented to the viewer. The tens of artists who took part in these exhibitions also came into prominence with their solo exhibitions, initiating the post-modern process and forming, however small, a following. The Association of the Mimar Sinan University Painting and Sculpture Museums, founded in 1979, also inaugurated the ongoing exhibitions titled Contemporary Artists in order to discover and support each period’s new generation of artists, emphasizing experimental, investigative and conceptual works. The uncompromising manner in which from 1987 onwards the Istanbul Biennial opened its doors to the contemporary movements and artists of the international environment also supported this transitory phase from a position of a receiver into provider.

2.

Despite these developments in the 1970s and early 1980s, it has to be stated that because of the well-documented political and economic isolation and lack of scientific and technological communication, a disconnection that was difficult to overcome existed between the landscape of local art and art in the outer world. As the Post-modern process began in the outer world; inside, there was an art environment that was suffocated and oppressed by political, social and economic conditions, or that forced the artist towards a politically radical stance. After 1955, in Western Europe and the US, the Modernist movements that had become vehicles of the system they initially opposed and lost their avant-garde qualities, were being surpassed and new and potent movements originate by Dada and Marcel Duchamp such as New Objectivism Pop-Art, Zero, Fluxus were emerging. It was becoming evident that the artwork was not a sterile human production but a product of visual thought in the fields that formed the intersections or nodes of communication networks.

Standard, eurocentric art history states that Conceptual Art is the last in a series of art movements that emerged after World War II, in the 1960s; however, looking back today, we see that such art historical assertions of an absolute nature have lost much validity. A broader view may conclude that Conceptual Art first appeared in the early 20th century: Marcel Duchamp’s exhibition in 1913 of the ready-made “Fountain” at the Armory Show in New York, Moholy-Nagy pointing to the power of communication by exhibiting the three Telephone Paintings side-by-side at the Der Sturm exhibition in 1924, Keith Arnatt using the sentence “I’m A Real Artist” as an artwork in 1972, and Hannah Höch’s publication of an artist’s book featuring her own collages in 1933 are the formed the theoretical bases of Conceptual Art.

It is generally stated that the term ‘conceptual art’ was first used by Edward Kienholz in the 1950s, and that it was redefined by Joseph Kosuth and Sol LeWitt in the 1960s. Roberta Smith indicates that conceptual art is the broadest, most rapidly developing and truly international 20th century art movement because of its openness to communication and because it includes language, reproduced images and diverse media and materials, yet she restricts the international scope this would appear to imply to Europe and North and South America. This is understandable in the context of the lack of communication in the divided nature of the world at the time she wrote this text. Despite no fundamental changes in terms of content, form or aesthetics, beyond 1970, this type of production known as Post-conceptual and/or New-conceptual art. (4)

The new orientation of art in terms of concept, content and form is defined in 1968 in Lucy Lippard and John Chandler’s article titled “The Dematerialization of Art”. (5) These critics claimed that the practice of producing conceptual art prioritized the thought process over the object in the creation of the artwork. This statement was based on a list including George Brecht’s Fluxus events, Allan Kaprow’s happenings, Bruce Nauman’s early videos, Gilbert & George’s prints, Robert Smithson and Richard Long’s land art pieces and the works of Kosuth, Sol LeWitt, Robert Barry and Vito Acconci. For instance, Robert Barry’s release on 3 March 1969 of a litre of krypton into the atmosphere (6), the first works of Sol LeWitt exhibited in 1963 at St. Mark’s Church in New York and his first solo exhibition in 1965 at the John Daniels Gallery and On Kawara’s commencement of his Date Paintings in 1966 were all included in this definition. In these works, the focus is on recording a process rather than producing a final object. How is it possible to show to the public an artwork that has been produced without a resulting finalised object? Artists came up with several ways of solving this problem: highlighting the idea, which was considered the purpose of the production of the work, removing the emphasis from visual/practical production and relinquishing the sublime and sterile form imposed by Modernist rules. This is how Sol LeWitt expressed his view on art in “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art”, a text he wrote in 1967 (7): “No matter what form it may finally have it must begin with an idea. (…) When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art.”

The second generalization points to the claim that the origins of Conceptual Art are solely in the US and the UK, and this has proven to be false in the framework of current research. The political, social and economic conditions of the period led to similar developments not only in Western Europe and the US, but also in many countries of the Eastern Bloc (Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, the Caucasus and Asia) and it is known that despite the lack of communication and closed borders in the Cold War era, artists somehow continued to be inspired by one another.

For instance, from the 1960s on, Conceptual Art in Soviet Russia emerged as a mode of underground production to the extent it was tolerated by official policies. Erik Bulatov, Ilya Kabakov, Komar and Melamid, Alexander Kosolapov, Igor Makarevich and Jelena Jelagina, , Boris Mikhailov, Dmitri Prigov, Leonid Sokov and Vadim Zakharov formed the group known as the Moscow Conceptualists, pioneered by Andrej Monastyrskij . They appropriated the right to criticism, which during that period solely belonged to the Communist Party and expressed this criticism through performances, installations and texts. The works of these artists, which sought a way of individual existence in the Soviet system that ignored them completely, reflected complex and intricate mythologies and biographies. These works also form an artistic archive about the impasses of everyday Soviet life, and remain outside the official view that glorifies the Soviet utopia. The Moscow Conceptualists were introduced (to the rest of the world) through the books of Boris Groys who immigrated to Germany in 1981. The “Total Enlightenment” exhibition held in 2008 at the Frankfurt Schirn Kunsthalle was the first collective display of the production in Moscow spanning the period from 1960 to 1990. (8) There is no museum that has an exhaustive collection of the works of the Moscow Conceptualists; their production can be featured at exhibitions only by borrowing works from various collections. From 1974 to 1989, conceptualists such as Vitali Komar, Alexander Melamid, Viktor Pivovarov, Oskar Rabin, Leonid Sokov, Michail Tschernyschov, Boris Groys, Ilya Kabakov and Yuri Albert left the Soviet world and became famous. Finally, in 2011 Andrej Monastyrskij was honoured in Venice Biennale in the Pavilion of Russia.

A similar development was taking place in Yugoslavia, our neighbouring country with which we had no political, social or cultural relationship during that period. The Slovenian group OHO, formed of poets, visual artists and film directors who were unhappy with the life-style, world order, the socialist order and the state of art of the times, was active between the years 1965 and 1970. Their interdisciplinary and multimedia artworks were primarily in the field of conceptual art and also included performance, concrete and visual poetry, mail art, arte povera and experimental film. OHO published books and contribute to magazines such as Perspektive, Tribuna, Problemi and to the Znamenja Editions. Their art upheld principles such as holism, spontaneity, autonomy and immediacy. The group was fortunate to be invited to an exhibition at MoMA in 1970; however they eventually dispersed, believing they had become increasingly institutionalized. The core members of OHO were Mark Pogacnik, Iztok Geister Plamen and Marjan Ciglic; who were later collaborated with Ivo Volaric-Feo, Slavoj Zizek, Braco Rotar, Bojan Brecelj, Drago Dellabernardina, Dimitrij Rupel and Rudi Seligo. An important collection of the works of OHO belongs to Marinko Sudac. (9)

The change of orientation that took place from 1960 to 1980 in our neighbour Romania despite all the prohibitions of the Ceauşescu regime was realized with a limited audience and mostly in artists’ studios in cities other than Bucarest (in the Transylvania and Banat). Paul Neagu, Pavel İlie, Andre Cadere and Ion Grigorescu, the leading artists of this movement, focused on everyday life experiences and performances particularly with Dada-source production. (10)

In terms of processes of Modernism and Post-modernism, similar developments in African countries that were not visible on the agenda until the 2000s were acknowledged following the exhibition titled “The Short Century. Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa 1945-1994” curated by Okwui Enwezor, first held at PS1 in New York in 2002, and later in Germany. (11)

These examples show that the break from Modernity took place in a broad geographical zone in a period from 1960 to 1980; and that the foundations of Post-Modernism and the transition to globalism were laid in the context of conceptual art, installations and performance art. Clearly, conceptual art in Turkey is simultaneous with and displays similarities to these examples: In Turkey too, the production took place outside Modernism, the political order, social consensuses, the way of seeing and perceiving art and the official view on art; meanwhile it changed the status of art. In the abovementioned countries, because of the prohibitive conditions implemented by the political authority, this change was neither sufficiently documented nor was it presented to the masses. Polarized global conditions meant that the development of a theory that embraced and assessed this non-Western production was delayed until the mid-1990s. Meanwhile, both society and the international art experts failed to fully appreciate the developments in Turkey at the time. The international art scene showed interest in the arts of the countries of the so-called periphery only after 1990, when ethnic identities and post-media production that examined different styles of everyday life became attractive. In this context, we must thank everyone who documented this production with their essays and research.

3.

The textual, visual and material qualities we see in the artworks of the six artists in this exhibition can be examined under the two main headings of analytic and synthetic: Some works feature one of the two methods, in others, the two methods are combined in the same work.

The analytic approach aims to extricate the most fundamental elements of the meaning and function, the universal or local, social or natural order of the artwork and of the physical, temporal and semantic variables of the space it is placed in by using visual and material means. The approach of Post-analytic Philosophy pioneered by Wittgenstein that crystallized in the 1960s, also referred to as Eclecticism and Pluralism, relied heavily on assumptions and evidence, shunned ambiguity and attached importance to detail; it also formed the basis of analytic production. (12)

A distinction should be made between this type of production and the analytic/synthetic production that continues to form the structural texture of art today: The body of conceptual art production in the 1970s and 1980s was quite removed from a first-hand sociological approach, from micro-scale research on popular culture or everyday life and from an attempt to come to terms with the visual material produced by mass media; moreover, it did not promote locality. Both the theoretical and the practical processes of production take place on a macro-scale and the universal space-time equation is of significance. In the works of these artists, the extrication of the social, political and natural elements of the system and the scrutiny of the concepts that pertain to them negates direct allusion. Analysis and synthesis are structured upon the philosophical and conceptual relationships between language and visual and material elements. While cognitive (cerebral) work involves analytic processes, the visualization and objectivization of thought and the relationship with space involves synthesis.

It is necessary to refer to Kant in order to understand the synthetic approach inherent in the cognitive process. Regarding the transition from the concept of the transcendent to the concept of the transcendental that he postulated, Kant states that “there is no transcendent knowledge, but there is transcendental knowledge”. Kant determines the transcendental duty of cognition as synthesis. If cognition (the mind) did not carry out this task, neither data provided by the senses, nor the contribution of sensibility could realize scientific knowledge. The mind carries out the task of synthesis by arranging the instruments of knowledge that are acquired with the help of sensibility. According to Kant, knowledge is derived not at the level of objects, but within the mind’s organization of thought processes. This is how Kant invented the transcendental method of thinking (Die Transzendentale Methode) (13).

The use of these two methods proved that, in the production of artworks, the cognitive process was as important as the final product. This comment does not mean that artists must produce their works by making use of these schools of philosophical thought; rather, it highlights how this type of production overlaps with universal currents and discourses of thought and that artists are competent and indeed, pioneers in this regard. We could assess the installations shown in this exhibition from this viewpoint and call them first thoughts and first works; the artists produced these works for group exhibitions, they would find the means to open solo exhibitions much later, in the 1990s.

Erdağ Aksel graduated from West Virginia University in 1977, and the three-dimensional installations he produced there in 1978 and 1979 were examples of the pioneering sculptural approach in the context of public space, environmental space and rural space. (14) In her 1979 essay titled “Sculpture in the Expanded Field”, (15) Rosalind Krauss deconstructs the transformation and change in the field of sculpture by presenting a series of examples of open-air installations that were a cross between the site-specific, the architectural and the non-architectural, and declares that the open-air installations with analytical and conceptual form and content created by artists such as Robert Morris, Richard Serra, Richard Long, Robert Smithson and Alice Aycock spelt the end of Modernist sculpture. The outdoor installations in Virginia that accentuated the characteristics of an area that Aksel had selected or that had been proposed to him, featuring measurements and schematic forms and mostly shaped using industrial materials are significant in terms of the artist’s knowledge and perception of the vision of art of his times. These installations reveal a desire to overcome (transcend) both the sterility of Modernism and the tendency to produce art-for-art’s-sake, and an effort towards postmodern expansion referred to by Krauss. A clear cognitive labour carried out with geometric lines or organic modules towards the formation of a visual/material outcome is evident in these works.

After returning to Turkey, Aksel held three solo exhibitions between 1985 and 1991 and took part in the important group exhibitions of the period. He displayed three groups of works in these exhibitions: The first group, Objects of Consumption, featured paintings of objects such as a television, an iron and a washing machine almost in the style of a sales catalogue and an installation consisting of an Arçelik washing machine with a wringer-dryer, that is included in this exhibition. With this work, Aksel exposed the mass-fetishization of durable consumer goods in consumption society, marking an economic and social breakthrough for Turkey. Home appliances were first used as ready-mades in early Pop-art. From 1964 onwards, Edward Kienholz, a pop-artist, produced dramatized installations re-staging the everyday life and household environment of US society, often using objects collected from flea markets. In the 1960s and after, objects of consumption, for instance the television, featured in the paintings of many artists; however, there are only a few examples that present these objects as ready-mades.

Considering it was from 1980 to 1985 that Jeff Koons exhibited the Hoover vacuum cleaner encased in plexiglas, the abovementioned artwork by Aksel proves that the artist met and confronted the realities of everyday life and the Turkey-version of such realities in a timely manner. His work in the industrial district of İzmir encouraged him towards collecting popular consumer goods as well. Therefore, it must be stated that Aksel is, in terms of using similar objects in order to examine consumption culture and using standard goods as ready-mades, the artist who, after Altan Gürman, pioneered this field. The second group of works is titled Objects of Tension; these works are handmade sculptures made by combining pieces of iron and bronze and various found objects. The third group features handmade collage sculptures made of assembled parts, examining and satirizing symbols with political-social allusions such as the obelisk and the star. These three groups of works inaugurated a new, irreversible movement as an alternative to Modernist sculpture that still endured at the time, despite having lost its validity as an art form.

Canan Beykal graduated from the Istanbul Fine Arts Academy Department of Painting in 1972 and was granted a certificate of proficiency for her thesis on the “Autonomy of Collage from Oil Painting”. In 1981 she studied at the Experimental Art Workshop of the Salzburg Summer Academy with Mario Merz, an important artist of the Arte Povera movement. These two achievements reveal that she had a clear goal from the very beginning. “A Cross-Section of Avant-Garde Turkish Art” and the “A, B, C” exhibitions became fields of application for her thoughts that had matured during these studies. The infrastructural deficiencies in the art scene of the period led Beykal to write essays theoretically advocating the artistic approach she had adopted. Her piece titled Isms, exhibited in 1981 at the State Fine Arts Gallery, is formed of a combination of hitherto uncommon elements such as language, text, graphic design and sound. In a corridor-like section of the gallery, a strip of paper approximately 10 metres long features various “-isms” stamped with ink.

These concepts were also read out both forwards and backwards and recorded on audiotape; the viewer listens to the recording while viewing the installation. Here we come across two cognitive dimensions: The first is the problem of nationalism which during that period in Turkey, could only be discussed in the context of the clash between the right and the left; and theTe problem of the other political –ism (anlam açık değil, -n.). Beykal proposes a post-structuralist approach to the problem. The second is the presentation of thought via the linguistic images of cognitive and fundamental concepts rather than the narrative and symbolic tools of painting. A similar approach can be traced in an analysis of painting at the “2nd Cross-Section of Avant-Garde Turkish Art Exhibition” held in 1985. The photographs Beykal exhibits – this is also the first time photography was exhibited as an artwork of this kind – were photographs showing the reverse side of 8 Osman Hamdi paintings, and feature the museum registry numbers of the paintings, and gold spray paint. This installation questions the unwavering and unchallengeable authority of traditional painting – in this instance an Orientalist painting – and the museum as an institution. This work can be compared to a 1973 painting by Marcel Broodthaers, who in his works criticized the museum as an institution. As a reference to Magritte whose paintings featuring text he greatly admired, Broodthaers wrote a word on each of 9 canvasses: these were words related to painting, such as style, colour, etc. (16)

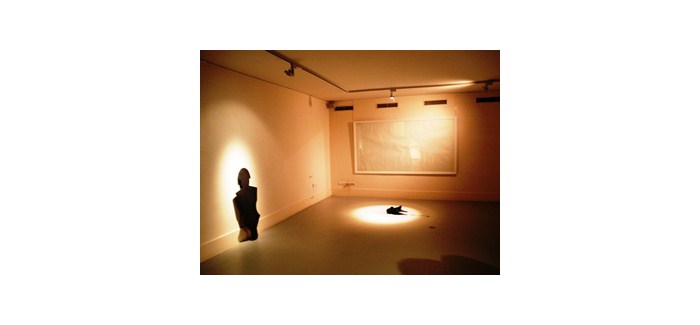

In 1989, Beykal produced an installation titled Tex-Toile and Black Boxes for the exhibition “10 Artists 10 Works: A”. The installation was formed of three black boxes: A box containing Beykal’s own boxes; a second box containing texts by writers who had committed suicide such as Von Kleist, Plath and Mayakovsky; and in a third box original voice recordings of Hitler, Goebbels and Marinetti. The juxtaposition of these figures is interesting for its period. This work, in turn, examines the destructive political and constructive artistic powers of 20th Century Modernism and their impact on the individual through text (literary texts) and voice (sound recordings). The title of the work also features an uncommon pun: the words text and canvas have been synthesized to form the word; however, a letter is missing in both words, therefore they are meaningless. However, this deficiency also adds a contradictory dimension to this artificial word: The paradox between representation through text and painting is highlighted. Another installation that continues this discourse emphasizing the relationship between language and visual thought is the work produced for the “8 Artists 8 Works: B” exhibition titled Everything nothing something featuring 15 light-boxes (1990). The potential syntheses of the words everything, nothing and something produce new meanings. The analyses and syntheses of words in these works trigger a thought process about the social-political-cultural meanings of words. With these works, Beykal paves the way for the development of post-structuralist / postmodern art production in Turkey.

Returning to Turkey in 1991, following a period of visual arts education at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Grenoble and the Institut des Hautes Etudes en Art Plastiques in Paris, Selim Birsel took part in the exhibitions of the pioneers of conceptual art. He was invited to the “8 Artists 8 Works: B” exhibition organized by the A Cross-Section of Avant-Garde Turkish Art group and produced his work titled Open Your Space, the final work of a series from what the artist himself chooses to call his Blue period, which is in fact a series of works based around the type of dark blue paper used for wrapping, covering or protecting from exposure to light.

Even this early work reveals the intellectual framework he has sustained to this day: Artistic production is the re-staging of the realities, events and knowledge of life using the techniques of seeing and showing. Birsel uses the art-historical memory of Fluxus and New Objectivism to realize this fictionalization. It would only be natural to say that, since he studied in France, the influences of French Conceptualists such as Yves Klein, Daniel Buren and Christian Boltanski and also the influences of Pino Pascali, Mario Merz, Giovanni Anselmo and Michelangelo Pistoletto from the Italian Arte Povera movement are traceable in Birsel’s works; but we also see that in adopting and transforming these influences, Birsel makes his own discourses clearer. In the installations he produced until around the 2000s, Birsel examines the problem of war without direct reference, indicating an implicit political stance, as in the works exhibited here.

Birsel’s first sketches are pastel-coloured tank figures, produced using the technique of potato/celery printing (5 Canonical Elements), reflecting the strange state of mind of a child’s imagination, wavering between play and war. In the next stage, a process related to seeing, failing to see, and not being seen can be traced in the black and white schematic drawings of F-117A (Stealth Fighter) war-planes and the wall installations featuring these drawings. Here we need to reference Paul Virilio. In his book titled “War and Cinema” Virilio spoke of how contemporary images played a role in crises, or indeed created them (17). He discusses how images become weapons, and how with the development of war technology the eye and the sense of seeing become weapons. Virilio points towards a new form of camouflage. Visibility has taken on various forms, such as visibility in terms of the naked eye, or visibility with/through an electronic device. Birsel chooses to use the F-117A, also known as the stealth fighter, in his work, because this warplane can not be tracked by radar, yet it leaves the viewer faced with death when seen with the naked eye. If new problems/conflicts are born of this new electronic system of visualization, we could perhaps render the world around us invisible and protect it from harm; in other words, we could create an aesthetics of invisibility. In his Blue period, during which he used blue wrapping paper and in his Black and White Period, when he used graphite, a soft drawing material, Birsel created an aesthetics of seeing, being seen, not being seen. With this method of production, Birsel established a relationship between the meta-material or meta-objective visualization methods of Suprematism to indicate his relationship with the fundamental principles of conceptual art.

For instance, Pilot and Open Your Space were included in the Europe Unknown exhibition held in Krakow in 1992. This work was formed of a wall with two sides. The front (visible/open) side featured the vaporous silhouette of a black F-117A below a vertical and horizontal organization formed of semi-transparent microporous medical bandages. The reverse side (invisible/closed) featured a painting-surface painted and polished entirely with black graphite. This is a conceptual-painterly solution for the dialectics of the visible/invisible. Two other works that pursue the same line of thinking are “5 Canonical Elements” (1992) a work comprising 5 weapons/cannons covered with semi-transparent white cloths and “Subversion” (1994), a work in which the black stovepipes that penetrate a soft-edged cube formed by surrounding four columns with white fibre represent a system which we can never see inside or know about.

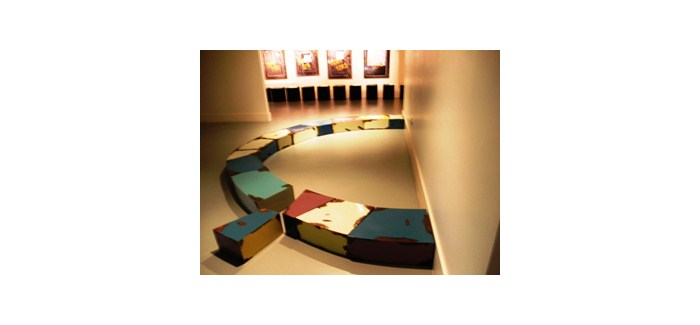

This exhibition features one of the most interesting works produced during this process. A white-on-white depiction of a tank produced by subjecting drawing paper to a sanding process, and in front of it, a wheeled toy painted with graphite; the viewer can play with the toy, and the sound the toy makes is such that it provides the viewer with the intended connotation. In the first installations there is a minimalist but painterly order unique to Birsel; a wall constitutes a visual field for the installation: In Open Your Space, a corner of the exhibition space is covered with blue wrapping paper on an inclined plane, and a trompe l’oeil confronts the viewer with a playful but sarcastic form of seeing/showing. From a pictorial viewpoint, these works of Birsel from the 1990s, proposed a new logistics of seeing and revealing as an alternative to the Neo-Expressionist painting of the 1980s that reflected individual mythologies, subconscious processes and moments of everyday life.

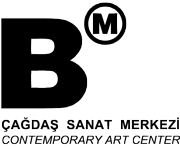

The exhibition presents the installations titled “Here and There” (1989) and “The Stars of Hipparchus” (1992) by Ayşe Erkmen. These early works of Erkmen show how the installation realizes itself as an artwork in opposition to sculpture and the readymade, and/or alongside them. One of Erkmen’s first works, “P.E.D.E.S.T.A.L” (1983) is a plain but intense piece; it is based around the idea of the tabula rasa. The plinth is the basis and the raison d’être of classical sculpture and if we again return to Rosalind Krauss, the logic of sculpture cannot be detached from the logic of the monument, and according to this logic, sculpture is a representation of memory. Krauss explains that this logic began to disappear with Rodin’s sculpture of Balzac: the body of the sculpture swallows and eradicates the pedestal, thus deterritorializing the sculpture and rendering it portable. She goes on to state that in the 1970s, works that would previously not have been classified as sculpture such as corridors, holes in the ground and mirrors placed in rooms began to be referred as sculpture (18). In 1983, the sculpture on a plinth, both as a monument and an abstract form, still retained its importance on the art scene in Turkey. As can be observed in the floor and wall pieces created earlier made out of stones left over from other sculptural work, entitled 100 Stones (1982) and Leftovers (1983), or the installation formed of simple iron rods marking the architectural data of the interior space of the Academy, decorated with sculptures, such as Harmonious Lines (1985), Erkmen displays an inclination to go beyond such restrictions. In her work titled P.E.D.E.S.T.A.L., (künyede aralarda nokta değil tire var, -n.) she places a simple pedestal painted white within a stone slab from which a square the size of the base of the pedestal has been removed, and goes on to place the extracted square piece on top of the pedestal. The classical materials for sculpture are wood and stone, and the actions of chiselling and cutting that form the classical sculpture are the analytic elements of sculpture; however, the monument/memory attribute of the sculpture has been cancelled by placing on the floor the stone piece that should have formed the body of the sculpture. Similar to the methods of Carl Andre, Donald Judd and Robert Morris, this is a distancing from the acts of chiselling, shaping and making, and is a characteristic of the change that defined the art of the developed industrial and late capitalist period in the 1960s and 1970s. In the 1980s, the capitalist system and industrialization in Turkey did not present the epistemological conditions for the emergence of this type of art. The works included in the exhibition, “Here and There” (1989) and “The Stars of Hipparchus” (1991), are two works that contribute to this change in terms of form and content. Erkmen realized her work titled “Here and There” for the Maçka Art Gallery, which was not designed simply as a white cube and encouraged every artist taking part in exhibitions there to produce site-specific works. The circular installation formed of metal boxes, competing with the architectural organization of the gallery based on a square-form and indicating an alternative to it that lies between the architectural and the non-architectural, is an uncommon spatial intervention for the time it was produced. In terms of the information it contains, “The Stars of Hipparchus” is an analytical piece – the work divides all the stars seen in the sky by Hipparchus in the year 129 B.C. into six categories according to their brightness. The installation is composed of metal plates featuring holes punctured according to the star map, scientific photographs and light. It completely overthrows the traditional characteristics of artwork production; the border between the process of artistic production and industrial design has been eradicated.

As a member of the Art Defition Group, Ahmet Öktem produced minimalist paintings. In an interview he explained these paintings by stating, “the small metal pipes I depicted in two or three dimensions as part of mechanical compositions, moved gradually away from being depictions and became object-forms in themselves”. (19) Aiming to swiftly distance his work from Modernism’s principles of representation and individual style, he began to work in photography as a medium; and this was the most impartial and detached type of photography. His installation formed of photography and documents at the Exhibition Art Definition Group held at the Beyoğlu Fine Arts Gallery (1970) was in line with the exhibition’s concept of rethinking (tabula rasa) the meaning and function of art and questioning art at the threshold of Postmodernism. This work by Öktem can be assessed from two different viewpoints. The first is the use of the absolute image of reality as a medium of association –the file cabinets and the life-size photographs of the file cabinets in this installation serve this function. The use here of both the real object and its image is a method of conceptual art practice undoubtedly pioneered by Joseph Kosuth. The second viewpoint is related to the political system of the period in which Öktem was living and it directly indicates deep bureaucracy, the problem of documentation inaccessible to the people that are its subjects; in other words, the problems of the democratization process. Öktem chooses the archival files and file cabinets, often only seen and used by those who are in charge of them as a medium that can place a visual emphasis on thought. Steel file cabinets full of archival files and/or the photographs of these cabinets, and the filed documents that the artist has collected – this is after all, a classified group of information – can only form a single association in the viewer’s mind, and also reduce the relationship between text (thought) and image (depiction) to a minimum. This trilogy including the real object, the photographic image of reality and the conceptual narrative of reality, is the fundamental procedure of conceptual art. This photographic and documentary installation is a powerful example of conceptual work from the period, and again, a first example in terms of the artistic use of photography.

Öktem continues to use the pre-information of the order and systems and the concept of the archive that forms its memory; however, from the 1990s on, he carries out interventions that develop in two directions with regard to his archive-related installations. The first is a pictorial procedure: A blue ink layer of stamps declaring a cancellation is spread out over archival facsimiles. The second is a technical intervention: Blue fluorescent light creates an integrative and inclusive effect encompassing all the photographs and structural details of the installation, but also an intensifying effect on the viewer’s perception. Öktem’s works must be assessed within a body of work that began with Moholy Nagy in the 1920s, addressed further in the 1960s by artists such as ZERO in Germany, GRAV in France and Gruppo T and Gruppo N in Italy and later realized with the use of diverse light sources and techniques in the context of conceptual art and installation art in the 1970s by artists such as Dan Flavin, Bruce Nauman, Keith Sonnier, James Turrell, Mario Merz, François Morellet and Maurizio Nannucci.

Serhat Kiraz received his art education in the 1970s at the State Fine Arts Academy, and as a young artist made an uncommon start to his career by participating in 1977 in the “Balkan Countries Plastic Arts Exhibition” and the “11th Paris Biennial” in 1980. From his early works produced in 1977-78 as a founding member of the Art Definition Group to his recent work, he has visualized the artwork not only as an object of perception but also as an object of philosophy. Kiraz synthesises within a geometrical, balanced, measured and cognitive installation structure, elements of painting, drawing, photography and various sources of light, these are all elements of the analytic outcome of the philosophy of art that is based on the idea that proclaims, “However complex and plural they may be, cultures emerge out of a single source, i.e., the human mind and imagination, therefore they must be assessed as a whole”. The golden ratio/the golden section, the fundamental concept of art history, forms the infrastructure of the scale and order of his installations. In many of his installations, he has indicated the relationship art has with historical knowledge, science and technology by using the Vitruvian Man, Leonardo da Vinci’s drawing depicting the golden ratio. The mathematical values of the golden ratio are also included in Kiraz’s works. Works such as Perception Under Visual Illusion and Reality, realized for the State Fine Arts Academy’s “New Tendencies Exhibition” in 1979, Untitled for the Exhibition Art Definition Group held at the Fine Arts Gallery in 1980 and A Proposal for Artistic Touristic Transport for the 11th Paris Biennial and the works at his solo exhibitions at the Maçka Art Gallery in 1984 and 1987 can be treated as parts of a gesamtkunstwerk that complement each other. In all of these works he uses photographs of objects, nature and cultural and political social events; photographs taken by the artist himself or licensed from various sources are installed in harmony with the space and in conformance with its physical qualities; every component of these installations has been produced and arranged to the highest levels of design, perfection and precise technical competence.

Kiraz’s installations are often composed of a three-dimensional structure in front of a wall painting/photograph; this synthesis of two-dimensional and three-dimensional works is a definitive method for his installations. For instance, in The God of Religions, The Religions of God (1989), the work he exhibited at the 2nd Istanbul Biennial features four glass displays containing the four holy books in front of a square structure formed out of fluorescent light fixtures. Region (1992) shown at the Sanat, Texnh exhibition features a labyrinthine structure is made of suspended glass light fixtures and organized according to the data derived from the star map on the wall it is placed in front of this map. This exhibition features Kiraz’s work shown at 10 Artists, 10 Works: D, the final exhibition of the A Cross-Section of Avant-Garde Turkish Art group held in 1993. Due to the conditions of the period, this final exhibition was held at the Koleksiyon Furniture store. Kiraz’s work titled Opposite was made of glass and neon lights. The 9 neon numbers, in the 3 main colours, placed between nine sheets of square glass attached to each other, resemble design objects such as a table or a box; this is a sign of the environmental relationship the artist has formed with the space in which the exhibition is held and the sense of illusion he evokes in the viewer. The numbers, alluding to mystical mathematical transactions of the Tarot and the Kabala, give the sum of 15 when added up in any direction. Referring to traditional knowledge and doctrine, this work also proposes the viewer to visually and objectively read the universal canonical knowledge used in everyday life in terms of contemporary techniques, materials and aesthetics.

The failure of both public and private cultural industry infrastructures to adequately exploit the possibilities created by the conceptually-based artworks and installations produced between 1977 and 1990 to produce art and articulate with international art movements and during all periods, the inaccessibility of the production reflecting this radical change to experts, young artists and the wider masses was a significant loss. After the mid-1990s, in an art environment that had experienced considerable emancipation in the context of political developments and entered into a process of global expansion thanks to advanced means of communication; the next generation of artists embarked upon a process of transforming the visual material produced by electronic media and consumer culture, focusing on sociological content such as the examination and critique of the structure of the nation-state, an emphasis on the crystallization of ethnic identities and the annotation of personal narratives. The progress of this generation to this stage and its recognition in the international arena would have been much more difficult without this body of work produced by the previous generation. This body of work that enabled an intellectual and formal change parallel and simultaneous to the artistic production in the USA, Europe and Eastern Bloc countries around Turkey from 1977 to 1990, laid the foundations of Istanbul’s current place on the global art map.

The exhibition titled “Timeless/Zeitlos” organized by Harald Szeemann in 1988 on the occasion of Berlin becoming the European Capital of Culture (20), laid Modernist art to rest and highlighted a new type of art production that sought a cerebral, sterile, expansive equilibrium between thought-space-time. As the production dates of the artworks in this exhibition reveal, a parallel production that created the same change in Turkey had entered its period of maturity by 1988. Szeemann’s following words could just as well have been spoken in relation to the artists in this exhibition: “The artists we exhibit at Timeless prefer their works to mean something on their own.” These artists retain these characteristics today.

- (Nilgün Özayten, Batı’da Obje Sanatı/Kavramsal Sanat/Post Kavramsal Sanat ve Türkiye’de 1965-1992 Yılları Arasındaki Benzer Eğilimler-Doktora Tezi, 1992)

- (N.Ö.a.y.)

- N.Ö 67-73)

- Roberta Smith, ‘Conceptual Art’ in Nikos Stangos, ed., Concepts of Modern Art, 1974, revised edn. 1981 ve Roberta Smith, Kavramsal Sanat,Resmi Görüş, Güncel Sanat Seçkisi, 3, yay.Vasıf Kortun, s.28 v.d.

- , John Chandler and Lucy Lippard ‘The Dematerialization of Art’,1968, Art International

- (http://www.frieze.com/issue/review/robert_barry,

- 7. http://www.examiner.com/museum-in-san-francisco/sfmoma-acquires-an-early-work-by-sol-lewitt

- http://www.artdaily.com/index.asp?int_sec=2&int_new=24825

- (www.avantgardemuseum.org)

- Ileana Pintilie: Conceptual Art on the Edge – Some Romanian Perspectives between the ’60’s and the 80’s http://www.vividradicalmemory.org/htm/workshop/stu_essays/pintilie_en.pdf

- http://ps1.org/exhibitions/view/193

- http://www.msxlabs.org/forum/felsefe/10437-analitik-felsefe-cozumleyici.html).

- http://hasat.org/forum/Kritisizm_=_Elestiricilik-k231.html

- 14. www.nesneler.com

- Rosalind Krauss. Sculpture in the Expanded Field, Postmodern Culture, ed. Hal Foster,Pluto Press, s.p.31-42

- 16. http://www.peterfreemaninc.com/exhibitions/three-works-by-marcel-broodthaers/pressrelease/

- Paul Virilio, War and Cinema: Logistics of Perception, Verso 1989, Preface to the English Edition,: The Sight Machine, 30 March 1988.

- Rosalind Krauss, a.y./ibid., s.p. 35

- Nilgün Özayten, s.p.113

- Zeitlos, Sergi Katalogu/Exhibition Catalogue, Werkstatt Berlin ve Prestel Verlag München, 1988, s.11